Your MDM Style Reveals Your Business Strategy

Every MDM style tells a story about how your organization defines truth.

During my consulting experience across fintech and insurance organizations, I’ve seen the same customer represented as multiple, conflicting records across CRM, billing, claims, and marketing systems.

In practice, this meant that Jane Smith in CRM appeared as J. Smith in billing, Jane A. Smith in claims, and as separate customer records with slightly different addresses in the marketing automation platform.

Each system claimed to be accurate. None provided a complete picture.

And when leadership asked simple questions—How many customers do we actually have? What’s our real exposure? Who should we target next?—the organization produced five answers. Then spent the next hour debating whose data was “correct.”

This wasn’t a data quality problem. It was a truth problem.

The conversation always shifted the same way: from fixing duplicates to implementing Master Data Management. But that’s when something more consequential emerged—a realization that stopped executives mid-sentence:

How you implement MDM matters just as much as whether you implement it at all.

What MDM Actually Solves (and Why It Gets Political)

Master Data Management sounds technical. Define your critical entities—customers, products, vendors, locations—then create a single source of truth by matching, merging, and governing data from multiple systems.

The concept feels straightforward: build a golden record. One best-available, trustworthy version of each entity.

But in practice, MDM forces uncomfortable questions:

- Who gets to create master data?

- Which system is authoritative for which attributes?

- How do you resolve conflicts when systems disagree?

- How quickly should changes propagate?

- What trade-offs between speed, autonomy, and control are acceptable?

These aren’t technical questions. They’re political questions—about power, ownership, and who controls truth in your organization.

Defining truth means redefining authority. Systems that operated independently become interdependent. Teams that owned their data must now negotiate it. The data architect who proposes centralized MDM is really saying: Your team no longer owns customer records.

This is why MDM implementation style is never neutral. It’s an operating model for truth—and a mirror reflecting how your organization actually functions.

The Four Implementation Styles—What They Really Mean

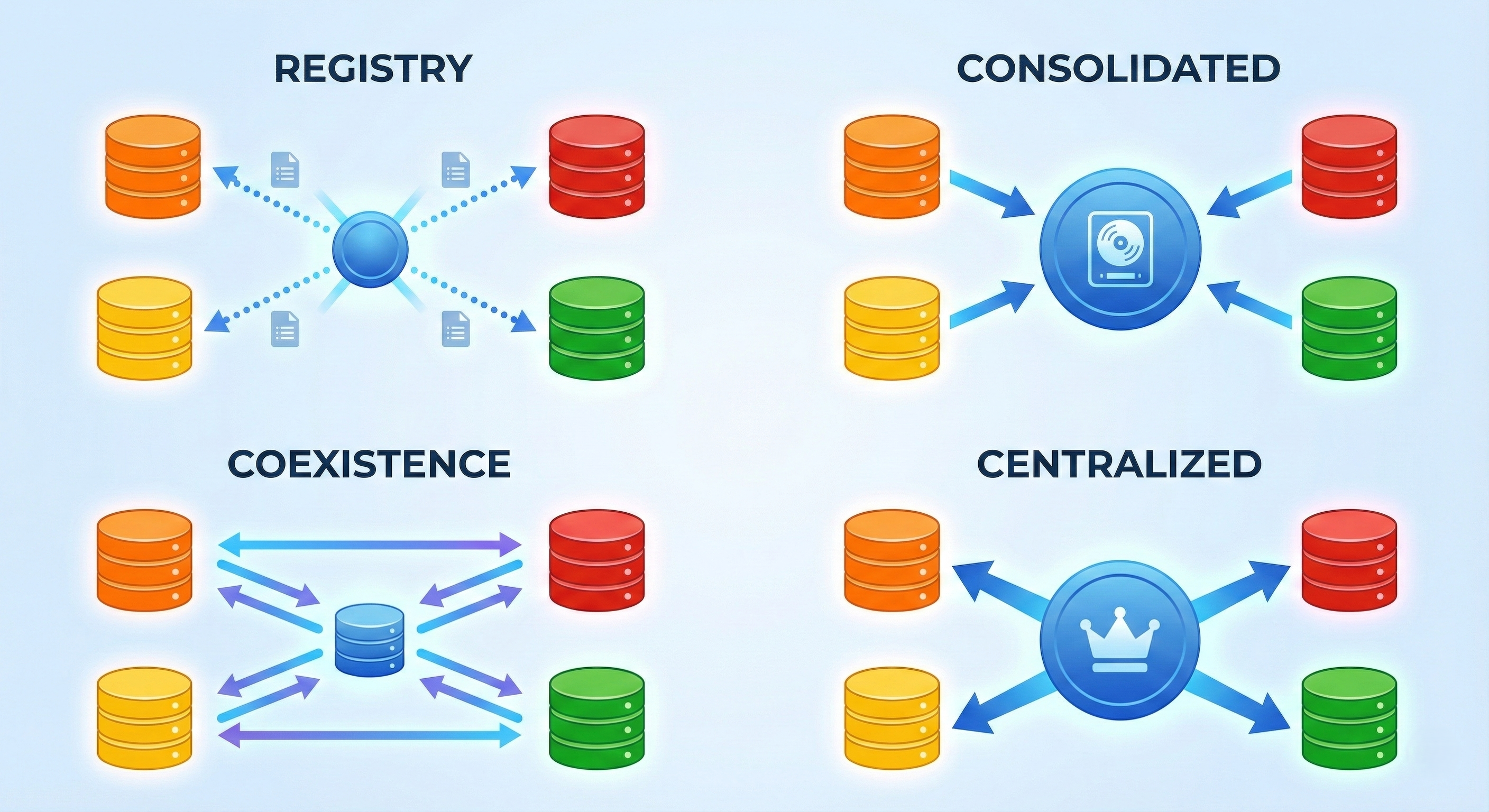

MDM styles are usually presented as architecture diagrams with arrows and boxes. But each represents a fundamentally different answer to: How much are we willing to change to achieve consistency?

The four MDM implementation styles represent different balances between governance, disruption, and organizational readiness

The four MDM implementation styles represent different balances between governance, disruption, and organizational readiness

Registry Style: Visibility Without Enforcement

The approach: Store identifiers and relationships. Source systems stay authoritative. Golden records are assembled virtually, on-demand.

What it signals: “We want to see our problems, but we’re not ready to fix them.”

Registry MDM is the least disruptive path. Perfect for organizations with low governance maturity or deeply decentralized cultures. You get cross-system visibility—you can finally see that Jane Smith exists five times—but you don’t force anyone to change.

The catch? Visibility without action becomes frustration. You expose inconsistencies faster than the organization can resolve them.

I’ve watched registry implementations succeed at building consensus for change. And I’ve watched them fail when leadership expected problems to fix themselves just because they were now visible.

Registry works when it’s step one—not the destination.

Consolidation Style: Truth for Analytics First

The approach: Copy data into a central hub. Cleanse, match, deduplicate. Create a golden record used primarily for reporting. Operational systems continue unchanged.

What it signals: “We need reliable numbers before we change how people work.”

Consolidation is the pragmatist’s choice. Common in banking, insurance, and retail where leadership desperately needs accurate customer counts, risk exposure, churn rates—but can’t afford to disrupt operations.

You deliver quick wins. Finance finally gets reliable revenue reports. Marketing can accurately calculate customer lifetime value. Risk management stops double-counting exposures.

But there’s a disconnect: analytics sees clean truth while operations lives with fragmentation.

The business analyst reviewing dashboards sees 1.2 million customers. The call center agent looking up a customer still sees duplicates. Eventually, someone asks: If we know the truth, why are we still working with lies?

Consolidation builds confidence and political capital. But it can’t stay consolidation forever.

Coexistence Style: Negotiated Truth Across Systems

The approach: The MDM hub holds the golden record. Source systems still create and update data. Changes sync bidirectionally.

What it signals: “We’re moving toward enterprise truth, but we respect local workflows—for now.”

Coexistence is the bridge between fragmentation and standardization. It’s how large organizations with significant legacy footprints actually implement MDM—because wholesale replacement isn’t realistic.

Sales can still create customers in Salesforce. The MDM hub receives that data, matches it against existing records, enriches it, and syncs the golden version back. Salesforce users don’t feel constrained. Enterprise analytics gets consistency.

But coexistence demands mature governance. When Salesforce and the billing system both update the same customer’s email address on the same day, who wins? Without clear rules, bidirectional sync becomes a battleground.

I’ve seen coexistence enable digital transformation—new systems onboard quickly while legacy systems gradually align. I’ve also seen it create expensive complexity when organizations tried it without the governance discipline to make conflict resolution decisions.

Coexistence works when you have both technical capability and organizational willingness to govern actively.

Centralized Style: Enforced Truth

The approach: The MDM hub is the only place master data is created and maintained. All downstream systems consume from it.

What it signals: “Consistency is mission-critical. We will reorganize workflows to achieve it.”

Centralized MDM delivers maximum consistency, auditability, and control. It’s the model regulated industries gravitate toward when compliance demands lineage, traceability, and proof of data quality.

When a bank implements centralized customer MDM, call center agents can’t create customer records anymore. They must use the MDM system—or integrate through it. Sales can’t bypass the process. Marketing can’t import lists without matching against the hub first.

This is powerful. It’s also unforgiving.

Without strong executive sponsorship and change management, centralized MDM becomes a bottleneck. Teams circumvent it. Shadow systems emerge. The very fragmentation you tried to eliminate returns—just hidden better.

Centralized MDM works when the organization is ready for it: strong governance culture, executive commitment, clear accountability, and workflows redesigned around the hub.

Attempted too early, it becomes rigidity mistaken for governance.

The Strategic Lenses Behind the Decision

In my consulting work, stakeholders rarely cite business theory explicitly. But their arguments always map to well-understood strategic concepts.

Data as Strategic Resource

Some organizations treat data as operational exhaust—necessary for reporting, not differentiating.

Others treat it as a core strategic asset that enables pricing optimization, personalization, risk management, competitive advantage.

When data is strategic, leadership invests in stronger MDM. Fragmentation isn’t just messy—it’s leaving money on the table.

I’ve watched this mindset drive organizations from consolidation toward coexistence, then centralization, once the value of unified data became undeniable.

The question isn’t Can we afford MDM? It’s: Can we afford not to fully exploit our data?

Change Readiness and Human Behavior

MDM changes how people work. Customer record creation. Duplicate handling. Exception resolution.

In organizations with low tolerance for disruption, aggressive MDM styles fail—not because the technology is wrong, but because behavior never changes.

I’ve seen coexistence succeed where centralized failed simply because teams weren’t ready to surrender autonomy. Conversely, I’ve seen centralized models work perfectly in heavily regulated environments where strict governance was already culturally embedded.

Your MDM style must match not just your ambition, but your change capacity.

Governance Maturity and Control

In insurance and banking, governance is often a feature, not a burden. Clear ownership, approval workflows, audit trails—already part of daily work.

In these environments, centralized or tightly governed coexistence feels natural. It aligns with existing bureaucratic structures.

In decentralized retail or fintech? Heavy enforcement triggers resistance. Teams prefer models that coordinate rather than dictate.

MDM cannot manufacture governance maturity. It can only amplify what already exists.

Agility and Adaptability

Businesses evolve constantly: new products, channels, acquisitions, regulations.

MDM should support adaptation—not slow it down.

Rigid architectures fossilize truth. Flexible ones let it evolve.

This is why dynamic environments favor coexistence. New systems onboard quickly while still moving toward consistency.

The test: Does this MDM approach help us move faster as we grow—or anchor us to the past?

External Pressure and Legitimacy

In regulated industries, MDM decisions are shaped by forces outside the organization: regulators, auditors, industry standards.

When compliance demands traceability and control, centralized models become unavoidable. MDM isn’t optimization—it’s a requirement for legitimacy.

Sometimes you don’t choose MDM because you want to. You choose it because the cost of not having it becomes existential.

A Practical Framework for Style Selection

Instead of asking “Which style is best?” ask:

Where must truth be enforced versus negotiated?

Not every domain needs the same rigor. Customer data might demand centralization. Product hierarchies might work fine with coexistence.

How much disruption can the organization absorb right now?

Honest assessment. Not aspirational. Not based on what the vendor demo promised.

Is the primary goal analytics, operations, or compliance?

Consolidation serves reporting. Coexistence serves operations. Centralization serves control.

What governance maturity actually exists today?

Not what you wish existed. What behaviors you can observe.

How quickly must the business adapt to change?

Rigid governance in a dynamic business creates tension. Loose governance in a stable business creates chaos.

In practice, successful programs evolve:

- Registry or consolidation to surface issues and build value

- Coexistence to align operations without breaking them

- Centralization for domains where control becomes non-negotiable

MDM is rarely a single decision. It’s a trajectory.

What This Really Means for Data Strategy

Data strategy is often described in terms of platforms and tools. But at its core, data strategy is about how an organization agrees on truth.

MDM makes that agreement explicit.

Every implementation style tells a story:

- Registry says: Connect first, understand the scope

- Consolidation says: Prove value before disrupting work

- Coexistence says: Align gradually while staying operational

- Centralized says: Consistency is non-negotiable

None is universally correct. Each reflects different balances between speed, control, autonomy, and accountability.

What matters is alignment.

When MDM style aligns with business strategy, governance maturity, and organizational culture, it becomes a foundation for confident decision-making.

When it doesn’t? It becomes an expensive attempt to organize disagreement.

The Conversation That Actually Matters

The most effective MDM programs I’ve seen didn’t start with tools or data models.

They started with honest conversations about how the organization wanted to operate.

They asked:

- What decisions matter most to us?

- Where does inconsistency actually hurt?

- Who must own truth—and who must consume it?

- What are we willing to change to get there?

These conversations are uncomfortable. They surface power dynamics. They force acknowledgment that today’s ways of working might not serve tomorrow’s ambitions.

But they’re the only conversations that matter.

Because MDM, done well, is not a technical fix.

It’s a strategic commitment.

And the implementation style you choose isn’t just an architectural decision—it’s a declaration of how your enterprise defines, governs, and acts on truth.

Have you navigated MDM implementation at your organization? I’d value hearing how strategic considerations shaped your approach. Connect with me on LinkedIn or reach out at athelivijay17@gmail.com.